Washington: While the globe is under the threat of a deadly virus, PREDICT assists man to think about the pandemics that hit the world in the past and at the same time, pandemics waiting to attack in the future. In 1918, world saw a situation like the present, when Spanish flu took the life of millions. Death was 20 million to 50 million.

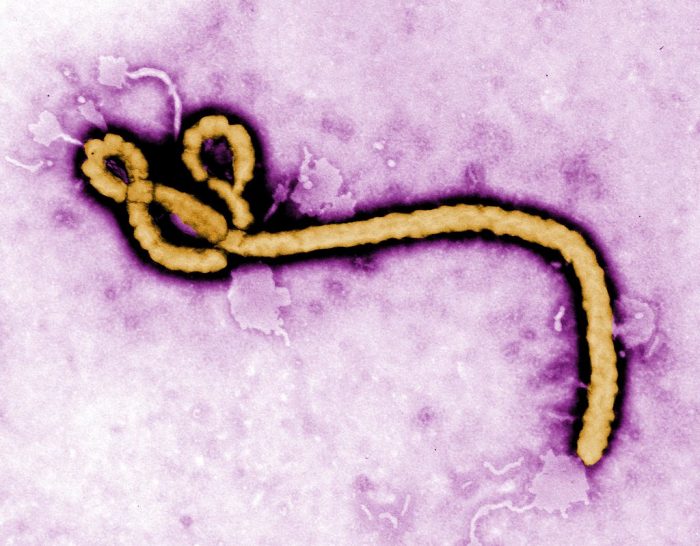

Spread of Ebola virus in 1970s that broke out in a small African village was another nightmare. People bled and died. Nipah, MERS – all threatened life in this planet. Scientists have compared the similarities in these viral outbreaks with the novel Corona virus called SARS Cov-2. Studies proved that all these viruses initially spread from animals that had carried these viruses. These diseases were called zoonoses.

Spanish flu likely came from birds. Researchers think that bats may have been the source of the Ebola virus and of Covid-19. “Roughly 75 percent of global pandemics and disease outbreaks caused by new viruses come from wild animals,” says Tracey Goldstein. She’s a virus detective at the University of California, Davis.

Supaporn Wacharapluesadee, faculty in the University of Bankok is another researcher who roam around forests, remote villages, and musk-scented caves across Thailand. She captured 932 bats in the early 2000s, drew their blood, released the animals, and returned to the lab to test for rabies-causing lyssaviruses. She then turned her attention to the deadly Nipah virus, which crossed from pigs to humans in Malaysia and Singapore in 1998 and Kerala in 2018.

Mission on contemporary pandemics:

For the past decade, Wacharapluesadee has collaborated with PREDICT, a U.S. Agency for International Development initiative to accelerate and coordinate global virus discovery and surveillance. The project has identified 949 novel viruses, created an extensive database of known viruses in wildlife, and trained nearly 7,000 scientists, lab technicians, and field workers to be on the lookout for emerging diseases. PREDICT also developed low-cost tools to test blood and other specimens from animals or humans for the genetic signatures of a virus family. Conventional tests look for a specific, known virus. These broader tests make it possible to identify a mystery virus by analyzing pieces of its DNA and matching the results to the genetic profiles of well-studied relatives.

Simon Anthony, an Assistant Professor of epidemiology at Columbia University, asked: “Of all the viruses out there, which have the genetic prerequisites to be able to infect people?” These questions drive Anthony’s research. In looking for answers, he has focused on two virus families: filoviruses, which include Ebola, and corona viruses, which include several common viruses that cause sniffles or coughs. Nobody recognized the corona virus family as a big problem until SARS. In 2018 he was part of a PREDICT team that identified a new Ebola virus, called Bombali, in free-tailed bats roosting inside people’s homes in Sierra Leone. Another research group soon found the virus in bats in Kenya, and a PREDICT team isolated it from bats in Guinea. “That tells us this virus is widely distributed, and we need to be able to be prepared,” said Tracey Goldstein, the PREDICT research leader.

About PREDICT:

PREDICT was established in 2009 to strengthen and coordinate what had been a hit-or-miss approach to discovering viral threats and improve the scientific and technical capabilities to monitor the danger in high-risk regions. The name suggested an early warning system, like an air-raid siren screeching at us to seek cover from incoming bombs, but that is a fanciful aspiration.

![The Top & Most Popular Seafood Bucket Restaurants in Dubai for you [Never Miss]](https://uae24x7.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/8-seafood-in-a-bucket-scaled-e1600739237403.jpg)

![Procedures for Renewing the Driving License in Abu Dhabi [3 Simple Steps]](https://uae24x7.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Capture-9-e1595666454466.jpg)